July 2, 1881: President James A. Garfield was only in office for four months before he was shot twice in an assassination attempt. The wound itself wasn’t initially fatal, but the process of removing the bullet led to infections that ultimately caused his death 80 days later.

James A. Garfield

President of the United States

Written and fact-checked by The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

James A. Garfield, in full James Abram Garfield, (born November 19, 1831, near Orange [in Cuyahoga county], Ohio, U.S.—died September 19, 1881, Elberon [now in Long Branch], New Jersey), 20th president of the United States (March 4–September 19, 1881), who had the second shortest tenure in U.S. presidential history. When he was shot and incapacitated, serious constitutional questions arose concerning who should properly perform the functions of the presidency.

Early life and political career

The last president born in a log cabin, Garfield was the son of Abram Garfield and Eliza Ballou, who continued to run the family’s impoverished Ohio farm after her husband’s death in 1833. Garfield dreamed of foreign ports of call as a sailor but instead worked for about six weeks guiding mules that pulled boats on the Ohio and Erie Canal, which ran from Lake Erie to the Ohio River. By his own estimate, Garfield, who did not know how to swim, fell into the canal some 16 times and contracted malaria in the process. Always studious, he attended Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later Hiram College) at Hiram, Ohio, and graduated (1856) from Williams College. He returned to the Eclectic Institute as a professor of ancient languages and in 1857, at age 25, became the school’s president. A year later he married Lucretia Rudolph (Lucretia Garfield) and began a family that included seven children (two died in infancy). Garfield also studied law and was ordained as a minister in the Disciples of Christ church, but he soon turned to politics.

An advocate of free-soil principles (opposing the extension of slavery), he became a supporter of the newly organized Republican Party and in 1859 was elected to the Ohio legislature. During the Civil War he helped recruit the 42nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry and became its colonel. After commanding a brigade at the Battle of Shiloh (April 1862), he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, and, while waiting for Congress to begin its session, he served as chief of staff in the Army of the Cumberland, winning promotion to major general after distinguishing himself at the Battle of Chickamauga (September 1863). It was about that time that Garfield had an extramarital affair with a Lucia Calhoun in New York City. He later admitted the indiscretion and was forgiven by his wife. Historians believe that the many letters he had written to Calhoun, which are referred to in his diary, were retrieved by Garfield and destroyed.

For nine terms, until 1880, Garfield represented Ohio’s 19th congressional district. As chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations, he became an expert on fiscal matters and advocated a high protective tariff, and, as a Radical Republican, he sought a firm policy of Reconstruction for the South. In 1880 the Ohio legislature elected him to the U.S. Senate.

Road to the presidency

At the Republican presidential convention the same year in Chicago, the delegates were divided into three principal camps: the “Stalwarts” (conservatives led by powerful New York Sen. Roscoe Conkling), who backed former president Ulysses S. Grant; the “Half-Breed” (moderate) supporters of Maine Sen. James G. Blaine; and those committed to Secretary of the Treasury John Sherman. Tall, bearded, affable, and eloquent, Garfield steered fellow Ohioan Sherman’s campaign and impressed so many with his largely extemporaneous nominating speech that he, not the candidate, became the focus of attention. As the chairman of the Ohio delegation, Garfield also led a coalition of anti-Grant delegates who succeeded in rescinding the unit rule, by which a majority of delegates from a state could cast the state’s entire vote. This victory added to Garfield’s prominence and doomed Grant’s candidacy. Grant led all other candidates for 35 ballots but failed to command a majority. On the 36th ballot the nomination went to a dark horse, Garfield, who was still trying to remove his name from nomination as the bandwagon gathered speed.

His Democratic opponent in the November 1880 general election was Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, like Garfield a Civil War veteran, so both could wrap themselves in the symbolic “bloody shirt” of the Union. But Garfield also capitalized on his rags-to-riches background, and, along with a campaign biography literally written by Horatio Alger, he reached back to his humble beginnings as a “canal boy” for the slogan “From the tow path to the White House.” (“No man ever started so low that accomplished so much, in all our history,” said former president Rutherford B. Hayes of Garfield. He was “the ideal self-made man.”) In an era when it was still considered unseemly for a candidate to court voters actively, Garfield, aided by Lucretia (who remained an important adviser), conducted the first “front porch” campaign, from his home in Mentor, Ohio, where reporters and voters came to hear him speak. Notwithstanding allegations of involvement in the Crédit Mobilier scandal, in which Garfield had received $329 from stock in the notorious company (a remuneration which Democrats characterized as a bribe and played up as a campaign issue by plastering walls, sidewalks, and placards with “329”), and a forged letter that supposedly revealed Garfield’s advocacy of unrestricted Chinese immigration, he defeated Hancock (as well as the third-party Greenback candidate), though he won the popular election by fewer than 10,000 votes. The vote in the electoral college was less close: 214 votes for Garfield, 155 for Hancock.

Presidency of James A. Garfield

By the time of his election, Garfield had begun to see education rather than the ballot box as the best hope for improving the lives of African Americans. In his inaugural speech he said, “The elevation of the Negro race from slavery to the full rights of citizenship is the most important political change we have known since the adoption of the Constitution of 1787. No thoughtful man can fail to appreciate its beneficent effect upon our institutions and people.…It has liberated the master as well as the slave from a relation which wronged and enfeebled both.”

Garfield tried to put together a cabinet that would appease all factions of the Republican Party, but, prompted by his secretary of state, Blaine, he eventually challenged Conkling’s patronage machine in New York. Instead of appointing one of Conkling’s friends as collector of the Port of New York, Garfield chose a Blaine protégé, prompting the resignation of an outraged Conkling and strengthening the independence and power of the presidency. So demanding were the office seekers and the pressures of the patronage system that at one point Garfield wondered why anyone would want to seek the presidency. “My God,” he exclaimed, “what is there in this place that a man should ever want to get into it!” The other significant development of Garfield’s short term of office, the Star Route scandal, involved the fraudulent dispersal of postal route contracts. “Go ahead regardless of where or whom you hit,” Garfield told investigators. “I direct you not only to probe this ulcer to the bottom, but to cut it out.” Despite such strong talk, Grant accused Garfield of having “the backbone of an angleworm.”

Assassination

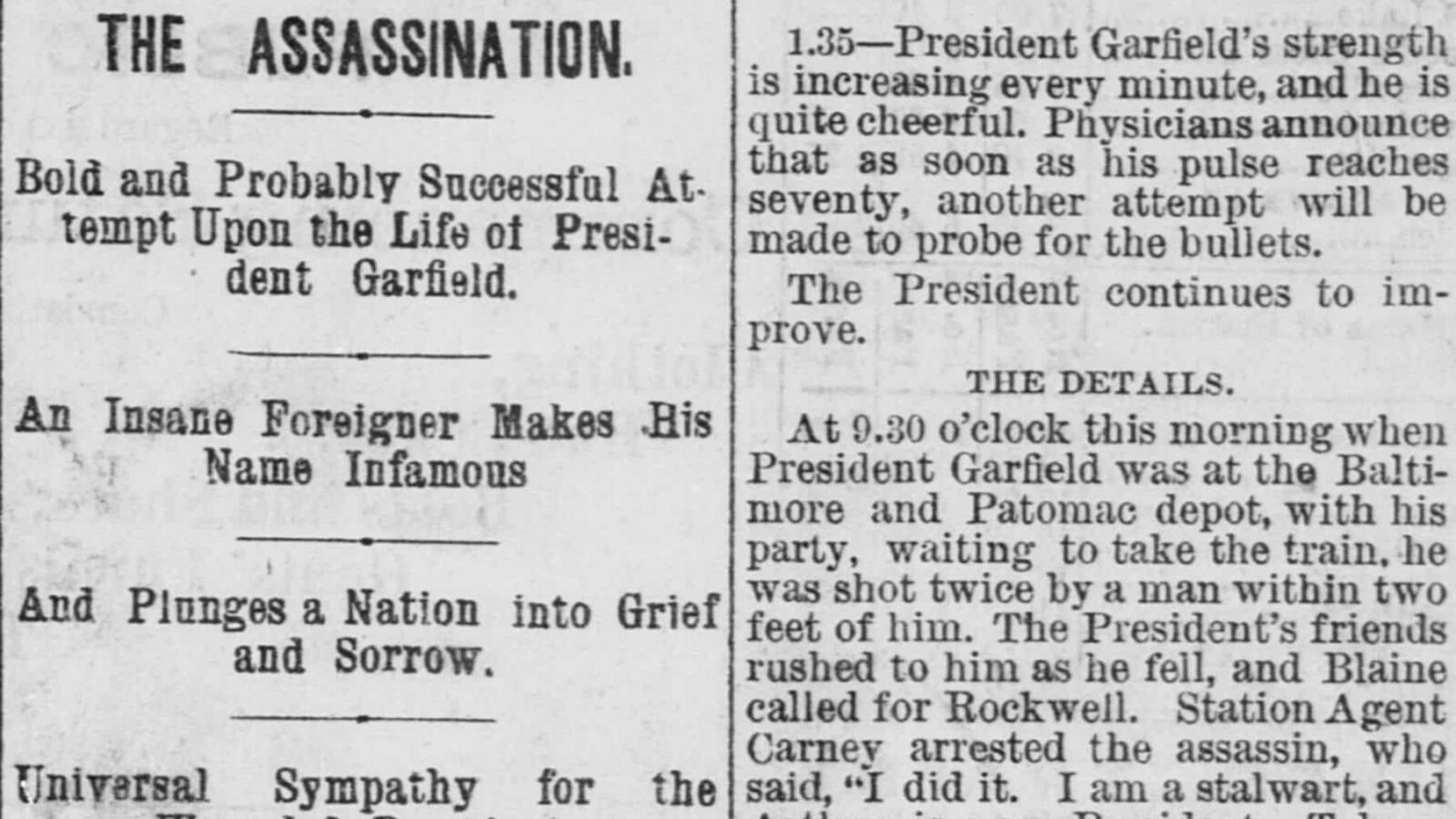

On July 2, 1881, after only four months in office, while on his way to a family vacation in New England, Garfield was shot twice in the railroad station in Washington, D.C., by Charles J. Guiteau, a disappointed office seeker with messianic visions. The first shot only grazed Garfield’s arm, but the second bullet pierced his back and lodged behind his pancreas. (In a letter dated November 1880, Garfield had written, “Assassination can be no more guarded against than death by lightning and it is not best to worry about either.”) Guiteau peaceably surrendered to police, calmly announcing, “I am a Stalwart. [Chester A.] Arthur is now president of the United States.”

In an era when the practice of medicine was largely oblivious of the role played by germs in illness and disease, a parade of doctors, both at the site of the shooting and in the hospital, poked and prodded Garfield’s wound in search of the bullet, heedless of the need for sterility and the danger of sepsis. The medical wisdom of the day dictated that the highest priority was the removal of the bullet, and a new invention by Alexander Graham Bell, the metal detector, was even brought in to aid in the search. In the process, Garfield’s body became ridden with an infection that would eventually take his life.

For 80 days the president lay ill and performed only one official act—the signing of an extradition paper. It was generally agreed that, in such cases, the vice president was empowered by the Constitution to assume the powers and duties of the office of president. But should he serve merely as acting president until Garfield recovered, or would he receive the office itself and thus displace his predecessor? Because of an ambiguity in the Constitution, opinion was divided, and, because Congress was not in session, the problem could not be debated there. On September 2, 1881, the matter came before a cabinet meeting, where it was finally agreed that no action would be taken without first consulting Garfield. But in the opinion of the doctors this was impossible, and no further action was taken before the death of the president on September 19, which was attributed to a fatal heart attack, massive hemorrhaging, and slow blood poisoning.

The public and the media were obsessed with this drawn-out passing of the president, leading historians to see in the brief Garfield administration the seeds of an important aspect of the modern president: the chief executive as celebrity and symbol of the nation. It is said that public mourning for Garfield was more extravagant than the grief displayed in the wake of Pres. Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, which is startling in light of the relative roles these men played in American history. Garfield was buried beneath a quarter-million-dollar 165-foot (50-metre) monument in Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland.