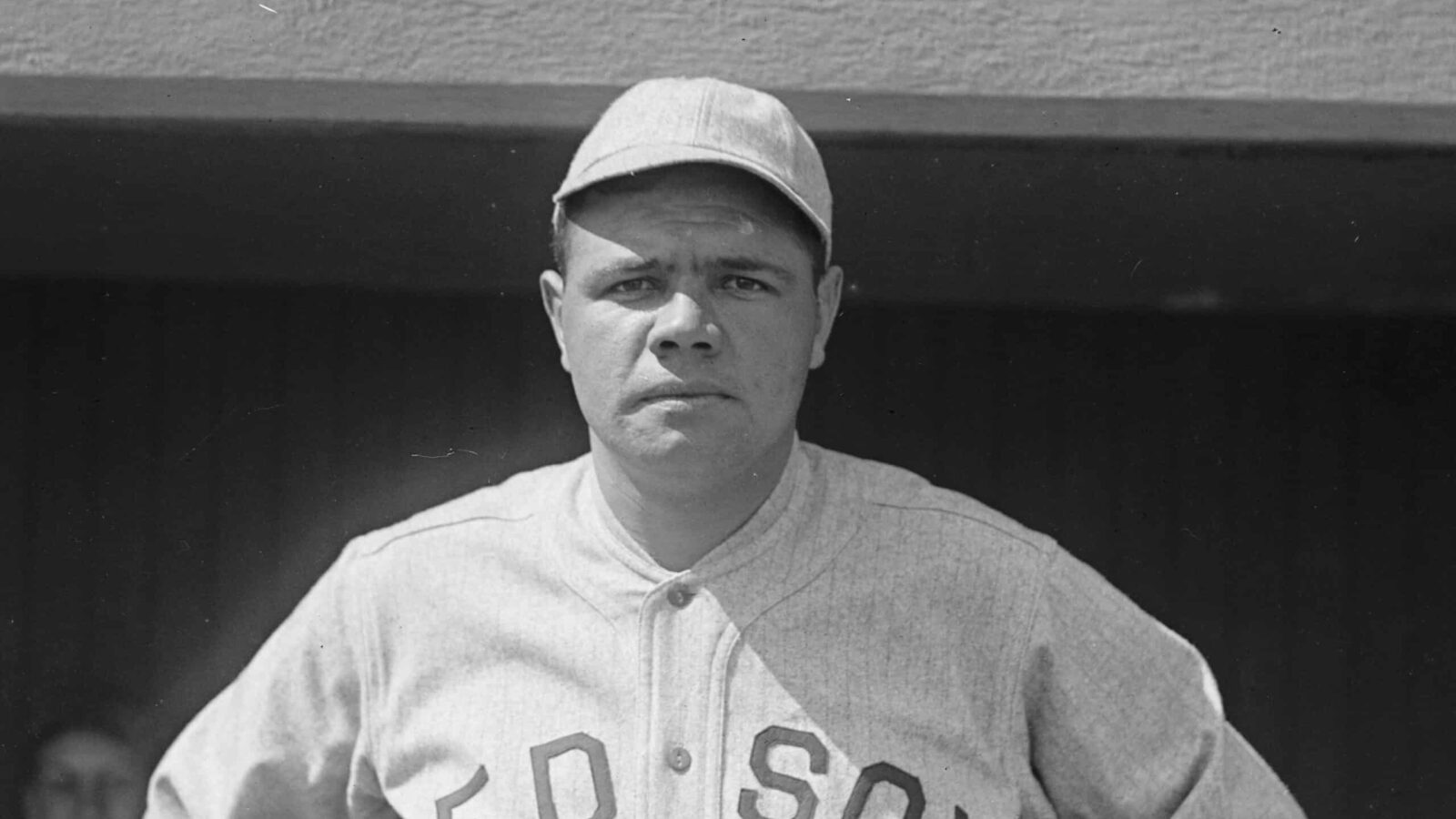

July 11, 1914: After throwing a no-hitter in a semi pro game, Babe Ruth was signed by the Baltimore Orioles owner-manager Jack Dunn. After a stellar spring showcase with the Orioles, Dunn sold Ruth, along with two other players, to the Boston Red Sox for $30,000. Babe Ruth started for the Red Sox the day after he arrived in a game against the Cleveland Naps.

July 11, 1914: Babe Ruth makes his major-league debut with Red Sox

This article was written by Joe Schuster

Even before playing an inning of major-league baseball, Babe Ruth was something of a legend.1

Partly this came from his on-field accomplishments. At age 19, just before the 1914 season, he joined the International League Baltimore Orioles, signed by owner-manager Jack Dunn after Dunn saw him throw a no-hitter in a 1913 semipro game in Baltimore.2 Ruth showed up eager for training camp, reportedly one of the first two to arrive,3 and was spectacular, especially in exhibitions against major-league clubs, showing himself “a sterling southpaw who (was) a terror to the big league clubs.”4

On March 25 against the Philadelphia Athletics, who’d win the 1914 AL pennant, he pitched “brilliantly” in a complete-game 6-2 victory against a lineup including Eddie Collins and Frank “Home Run” Baker.5 He also pitched well against the Dodgers, Braves, and Phillies, and continued his effectiveness into the season, shutting out Buffalo 6-0 in his April 22 regular-season debut.6

By June, partly because Ruth had a stretch of nine consecutive victories, several major-league teams expressed interest in acquiring him, including at least one from the Federal League.7 On July 9 Dunn sold him to the Boston Red Sox, along with Ernie Shore and Ben Egan, for a reported $30,000.8

The deal garnered significant attention, some of which furthered the idea of Ruth as legend. The Baltimore Sun, profiling him, emphasized his difficult childhood during which his parents had declared him incorrigible and deposited him at St. Mary’s Industrial school for delinquents; there, the Sun declared, Ruth blossomed into someone “heralded from one end of the country to the other as a wonderful man (whose) whole heart was put into baseball.”9 Announcing the deal, the Boston Globe dubbed him “the next (Rube) Waddell.”10

The team Ruth joined was in sixth place at 39-38 after losing its last five. Its woes stemmed partly from injury and illness. Among others, Joe Wood, who’d won 34 games in 1912, had a sore arm; Heinie Wagner, the team’s 1913 shortstop, would miss the season because of rheumatism; an infielder Boston acquired from Detroit, Del Gainer, injured himself almost immediately after arriving; pitcher Rube Foster hurt his knee; and the Red Sox’ best hitter, Tris Speaker, was “badly bunged up, though … sticking it out.”11 Announcing the deal, owner Joseph Lannin said he’d “let no expense stand in the way of putting the Red Sox in the American League race and keeping them there.”12

Because of the tattered pitching staff, Ruth did not have to wait long to see action, as manager Bill Carrigan started him the day he arrived, a Saturday afternoon contest against the Cleveland Naps, who at 26-49 were the worst team in the majors. Managed by Joe Birmingham, Cleveland featured outfielder Shoeless Joe Jackson (then hitting .333), and shortstop Ray Chapman, who was just beginning to find his way after starting the season late after breaking his leg in the spring.

Opposing Ruth was Willie Mitchell, 24 and in his sixth major-league season, with a 4-9 record and a 3.93 ERA. Mitchell was erratic. Although he would finish second in the league that year in strikeouts with 179, he’d also finish second in walks with 124.

Game day was pleasant; the Cleveland Plain Dealer described it as “an ideal summer afternoon (with) an east wind from Boston harbor tempering the heat.”13 The combination of weather and the chance to see Ruth drew 11,087 in paid attendance.14

Ruth’s day began oddly. He gave up a single to Jack Graney leading off, and a groundout by Terry Turner moved him to second before Jackson singled, but Graney attempted to score on Jackson’s hit, was caught in a rundown, and was out at the plate.15 On that play, Jackson tried for second, but was also thrown out. The Red Sox took the lead in the bottom of the inning. After Olaf Henriksen struck out leading off, Everett Scott singled. He was forced at second by Speaker’s grounder. Speaker then stole second, and scored on a triple by Larry Gardner.

Neither team did anything of consequence in the second and third innings, but the second featured Ruth’s first major-league at-bat, in which he struck out, though the Globe noted that he “received a perfect ovation when he went to the bat, and shaped up like a good batsman.”16

Cleveland tied it in the top of the fourth: Graney hit a long drive to deep center field that Speaker went after and got his glove on but could not corral, allowing Graney to reach second. The scorer ruled it an error but, the Plain Dealer reported, he “was a bit hard on Speaker. … (He) just reached it after a long run and most everybody in the press box regarded it as awfully close to a two-base hit.”17 Turner sacrificed Graney to third, and he scored on Jackson’s second single of the day.

Boston went back on top with a pair of two-out runs in the bottom of the inning. Gardner singled leading off and advanced to third on a sacrifice by Hal Janvrin and a groundout by Wally Rehg. Steve Yerkes walked and stole second. When catcher Steve O’Neill’s throw sailed into center field, Gardner scored. Carrigan (who was also the team’s starting catcher) followed with a double, driving in Yerkes, before Ruth ended the inning by flying out to Jackson in right.

The lead held until the seventh, when Cleveland tied the score on three singles: Jay Kirke led off with one and moved to second on another by Chapman. Nemo Leibold sacrificed, moving both to second and third, respectively, and they scored on a single by O’Neill. Ruth got out of the inning when Mitchell grounded to short for a double play.

That was the end of Ruth’s day. Duffy Lewis pinch-hit for him leading off the bottom of the seventh and grounded a roller to Kirke at first. When Kirke threw to Mitchell covering, the ball eluded the pitcher, letting Lewis reach second. After Henriksen flied out, Scott bounced back to Mitchell, who, instead of throwing to first for the out, went after Lewis, who was caught between second and third. Lewis managed to stay in a rundown long enough for Scott to advance to second. He came in on Speaker’s single. The inning ended with Speaker being caught trying to steal.

To relieve Ruth, Carrigan brought in Dutch Leonard, who was having the best year of his career (he would lead the league with a microscopic 0.96 ERA while going 19-5). He set down the last six Naps in order, striking out four, picking up his first save on the season, and giving Ruth his first major-league victory. Ruth’s final line: seven innings, eight hits, three runs (two earned), no walks, and one strikeout. Despite his faltering in the seventh and although noting that he could improve, the Globe praised him: “(He) proved a natural ballplayer and went through his act like a veteran of many wars. He has a natural delivery, fine control and a curve ball that bothers the batsmen.”18 Mitchell, the losing hurler, pitched at least as well as Ruth, going the distance and surrendering four runs (three earned) on eight hits and two walks, while striking out five.

Five days later, Ruth got his second start, this time against Detroit. He lasted three innings, allowing two earned runs on three hits and a walk, striking out one, and taking the loss. After he spent the next month on the bench without getting into a game, Boston sent him to the minors on August 18.

While his arrival was ballyhooed by long, laudatory newspaper articles, his departure was noted by almost a journalistic whisper, a single sentence on the bottom of the page in the August 18 edition of the Globe: “‘Babe’ Ruth, the ‘Southpaw’ pitcher who came to Boston from Baltimore, has been released to the Providence club of the International League.”19

He may have arrived in the majors described as a legend, but it would take some time before he would actually be one.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also relied on Baseball Reference for statistics, as well as the Society for American Baseball Research’s Biography Project for background information.

Notes

1 See, for example, C. Starr Matthews, “The Rise of Babe Ruth,” Baltimore Sun, July 10, 1914: 5, and J.C. O’Leary, “Three New Men for the Red Sox,” Boston Globe, July 10, 1914: 1.

2 O’Leary.

3 “Orioles to Leave for Camp Tonight,” Baltimore Evening Sun, March 2, 1914: 8.

4 “Giants in the Final Exhibition Game,” Baltimore Evening Sun, April 13, 1914: 2.

5 Jesse A. Linthicum, “Birds Beat Athletics,” Baltimore Sun, March 26, 1914: 5.

6 “Ruth Scores Shutout,” Baltimore Sun, April 23, 1914: 11.

7 “Federal League After Babe Ruth,” Baltimore Evening Sun, June 5, 1914: 8.

8 O’Leary.

9 Matthews.

10 O’Leary.

11 O’Leary.

12 Ibid.

13 “Red Sox Hits and Naps’ Errors Give Boston Game,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 12, 1914: II-1.

14 Ibid.

15 Play-by-play detail comes from the Boston Globe and Cleveland Plain Dealer accounts of the game.

16 T.H. Murnane, “Ruth Leads Red Sox to Victory, Boston Globe, July 12, 1914: 11.

17 “Features,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 12, 1914: 1B.

18 Murnane.

19 “Ruth Goes to Providence,” Boston Globe, August 18, 1914: 6.