June 23, 1865: Confederate General Stand Watie surrendered at Doaksville in the Choctaw Nation (present-day Oklahoma) by signing a cease-fire agreement with Union representatives. He led the First Indian Brigade of the Army of the Trans-Mississippi and is remembered as the last Confederate General to surrender during the American Civil War.

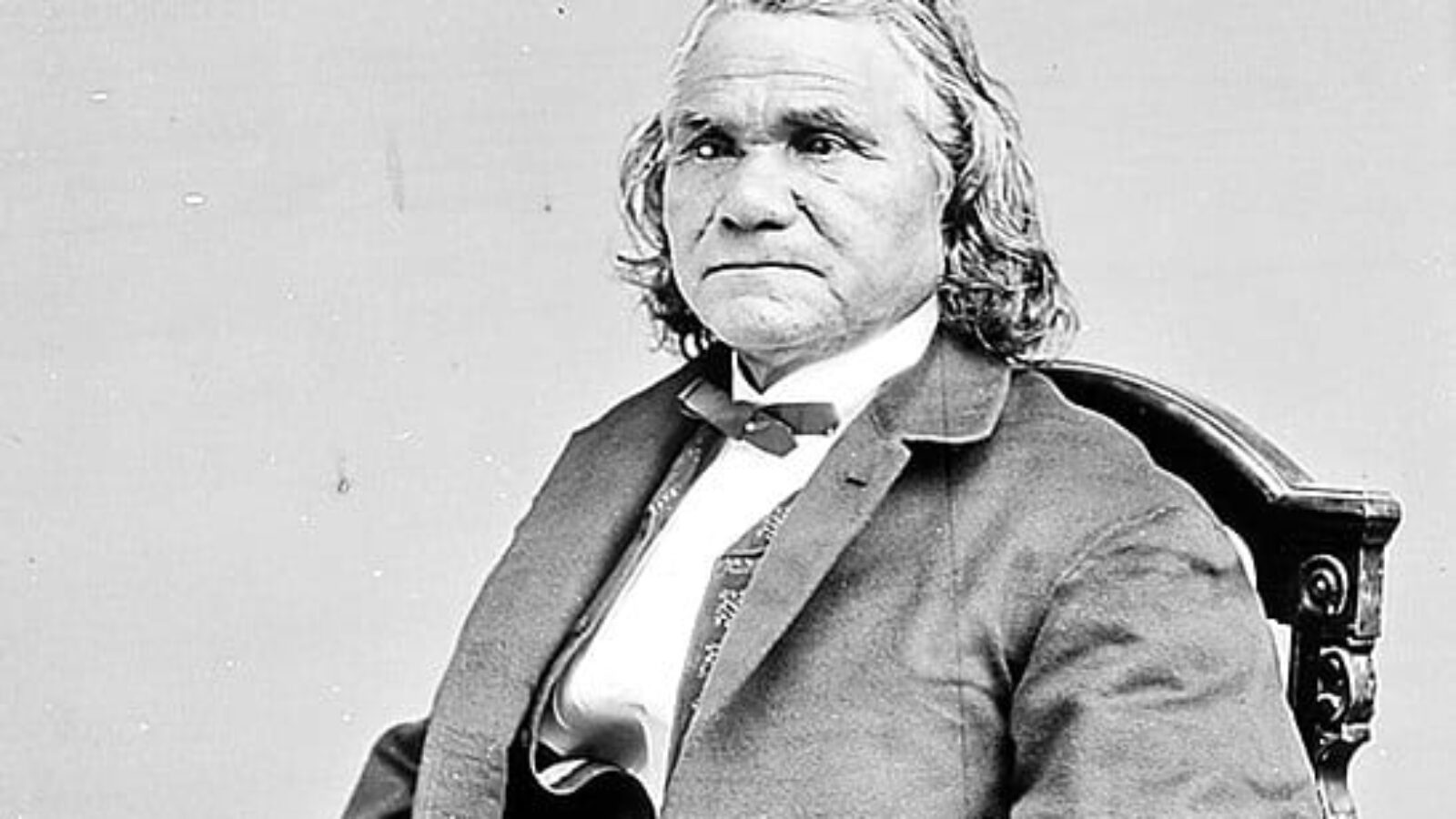

Stand Watie

Brigadier-General Stand Watie (Cherokee: ᏕᎦᏔᎦ, romanized: Degataga, lit. ’Stand firm’; December 12, 1806 – September 9, 1871), also known as Standhope Uwatie, Tawkertawker,[citation needed] and Isaac S. Watie, was a Cherokee politician who served as the second principal chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1862 to 1866. The Cherokee Nation allied with the Confederate States during the American Civil War and he was the only Native American Confederate general officer of the war. Watie commanded Indian forces in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, made up mostly of Cherokee, Muskogee, and Seminole. He was the last Confederate States Army general to surrender.

Before removal of the Cherokee to Indian Territory in the late 1830s, Watie and his older brother Elias Boudinot were among Cherokee leaders who signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835. The majority of the tribe opposed their action. In 1839, the brothers were attacked in an assassination attempt, as were other relatives active in the Treaty Party. All but Stand Watie were killed. Watie in 1842 killed one of his uncle’s attackers, and in 1845 his brother Thomas was killed in retaliation, in a continuing cycle of violence that reached Indian Territory. Watie was acquitted by the Cherokee at trial in the 1850s on the grounds of self-defense.

Watie led the Southern Cherokee delegation to Washington, D.C., after the American Civil War to sue for peace, hoping to have tribal divisions recognized. The federal government negotiated only with the leaders who had sided with the Union. Watie stayed out of politics for his last years, and tried to rebuild his plantation.

American Civil War

In 1861, Principal Chief John Ross signed an alliance with the Confederate States to avoid disunity in Indian Territory.[11] Within less than a year, Ross and part of the National Council concluded that the agreement had proved disastrous. In the summer of 1862, Ross removed the tribal records to Union-held Kansas and then proceeded to Washington, D.C., to meet with President Lincoln.[11] After Ross fled to Federal-controlled territory, Watie replaced him as principal chief.[1] After Ross’ departure, Tom Pegg took over as principal chief of the pro-Union Cherokee.[12] Following Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, Pegg called a special session of the Cherokee National Council. On February 18, 1863, it passed a resolution to emancipate all slaves within the boundaries of the Cherokee Nation.

After many Cherokee fled north to Kansas or south to Texas for safety, pro-Confederates took advantage of the instability and elected Stand Watie principal chief. Ross’ supporters refused to recognize the validity of the election. Open warfare broke out between Confederate and Union Cherokee within Indian Territory, the damage heightened by brigands with no allegiance at all.[13] After the Civil War ended, both factions sent delegations to Washington. Watie pushed for recognition of a separate “Southern Cherokee Nation”, but never achieved that.[1]

National Color of the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles

Watie was the only Native American to rise to a Confederate brigadier-general’s rank during the war. Fearful of the Federal Government and the threat to create a State (Oklahoma) out of most of what was then the semi-sovereign “Indian Territory”, a majority of the Cherokee Nation initially voted to support the Confederacy in the American Civil War for pragmatic reasons, though less than a tenth of the Cherokee owned slaves. Watie organized a regiment of mounted infantry. In October 1861, he was commissioned as colonel in what would become the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles.[14]

Although Watie fought Federal troops, he also led his men in fighting between factions of the Cherokee and in attacks on Cherokee civilians and farms, as well as against the Creek, Seminole and others in Indian Territory who chose to support the Union. Watie is noted for his role in the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, on March 6–8, 1862. Under the overall command of General Benjamin McCulloch, Watie’s troops captured Union artillery positions and covered the retreat of Confederate forces from the battlefield after the Union took control.[15] However, most of the Cherokees who had joined Colonel John Drew’s regiment defected to the Union side. Drew, a nephew of Chief Ross, remained loyal to the Confederacy.[15]

In August 1862, after John Ross and his followers announced their support for the Union and went to Fort Leavenworth, the remaining Southern Confederate minority faction elected Stand Watie as principal chief.[16] After Cherokee support for the Confederacy sharply declined, Watie continued to lead the remnant of his cavalry. He was appointed to the grade of Brigadier-General on May 10, 1864, with a date of rank of May 6,[14] though he did not receive word of his promotion until after he led the ambush of the steamboat J. R. Williams on July 16, 1864.[17] Watie commanded the First Indian Brigade of the Army of the Trans-Mississippi, composed of two regiments of Mounted Rifles and three battalions of Cherokee, Seminole and Osage infantry. These troops were based south of the Canadian River, and periodically crossed the river into Union territory.[citation needed]

They fought in a number of battles and skirmishes in the western Confederate states, including the Indian Territory, Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, and Texas. Watie’s force reportedly fought in more battles west of the Mississippi River than any other unit. Watie took part in what is considered to be the greatest (and most famous) Confederate victory in Indian Territory, the Second Battle of Cabin Creek, which took place in what is now Mayes County, Oklahoma on September 19, 1864. He and General Richard Montgomery Gano led a raid that captured a Federal wagon train and netted approximately $1 million worth of wagons, mules, commissary supplies, and other needed items.[18] Stand Watie’s forces massacred black haycutters at Wagoner, Oklahoma during this raid. Union reports said that Watie’s Indian cavalry “killed all the Negroes they could find”, including wounded men.[19]

Since most Cherokee were now Union supporters, during the war, General Watie’s family and other Confederate Cherokee took refuge in Rusk and Smith counties of east Texas.[20] The Cherokee and allied warriors became a potent Confederate fighting force that kept Union troops out of southern Indian Territory and large parts of north Texas throughout the war, but spent most of their time attacking other Cherokee.[citation needed]

The Confederate Army put Watie in command of the Indian Division of Indian Territory in February 1865. By then, however, the Confederates were no longer able to fight in the territory effectively.[1] On June 23, 1865, at Doaksville in the Choctaw Nation (now Oklahoma), Watie signed a cease-fire agreement with Union representatives for his command, the First Indian Brigade of the Army of the Trans-Mississippi. He was the last Confederate general in the field to surrender.[14][21][22]

In September 1865, after his demobilization, Watie went to Texas to see his wife Sallie and to mourn the death of their son, Comisky, who had died at age 15.[23] After the war, Watie was a member of the Cherokee Delegation to the Southern Treaty Commission, which renegotiated treaties with the United States.[24]